Ecofascism: What is It?

A Left Biocentric Analysis

By David Orton

Green Web Bulletin #68

February, 2000

Introduction

This bulletin is an examination of the term and concept of “ecofascism.” It is a strange term/ concept to really have any conceptual validity. While there have been in the past forms of government which were widely considered to be fascist - Hitler's Germany, Mussolini's Italy and Franco’s Spain, or Pinochet's Chile, there has never yet been a country that has had an “eco-fascist” government or, to my knowledge, a political organization which has declared itself publicly as organized on an ecofascist basis.

Fascism comes in many forms. Contemporary fascist-type movements (often an alliance of conservative and fascist forces), like the National Front (France), the Republicans (Germany), the Freedom Movement (Austria), the Flemish Block (Belgium), etc., may have ecological concerns, but these are not at the center of the various philosophies and are but one of a number of issues used to mobilize support - for example crime-fighting, globalization and economic competition, alleged loss of cultural identity because of large scale immigration, etc. For any organization which seeks some kind of popular support, even a fascist organization, it would be hard to ignore the environment. But these would be considered “shallow” not defining or “deep” concerns for deep ecology supporters. None of these or similar organizations call themselves ecofascists. (One time German Green Party member, ecologist Herbert Gruhl, who went on to form other political organizations, and to write the popular 1975 book A Planet Is Plundered: The Balance of Terror of Our Politics, did develop what seems to be an intermeshing of ecological and fascist ideas.) While for fascists, the term “fascist” will have positive connotations (of course not for the rest of us), “ecofascist” as used around the environmental and green movements, has no recognizable past or present political embodiment, and has only negative connotations. So the use of the term “ecofascism” in Canada or the United States is meant to convey an insult!

Many supporters of the deep ecology movement have been uncomfortable and on the defensive concerning the question of ecofascism, because of criticism levelled against them, such as for example from some supporters of social ecology, who present themselves as more knowledgeable on social matters. (The term “social ecology” implies this.) This bulletin is meant to change this situation. I will try to show why I have arrived at the conclusion, after investigation, that “ecofascism” has come to be used mainly as an attack term, with social ecology roots, against the deep ecology movement and its supporters plus, more generally, the environmental movement. Thus, “ecofascist” and “ecofascism”, are used not to enlighten but to smear.

Deep ecology has as a major and important focus the insight that the ecological crisis demands a basic change of values, the shift from human-centered anthropocentrism to ecocentrism and respect for the natural world. But critics from within the deep ecology movement (see for example the 1985 publication by the late Australian deep ecologist Richard Sylvan, A Critique of Deep Ecology and his subsequent writings like the 1994 book The Greening of Ethics, and the work by myself in various Green Web publications concerned with helping to outline the left biocentric theoretical tendency and the inherent radicalism within deep ecology), have pointed out that to create a mass movement informed by deep ecology, there must be an alternative cultural, social, and economic vision to that of industrial capitalist society, and a political theory for the mobilization of human society and to show the way forward. These are urgent and exciting tasks facing the deep ecology movement, and extend beyond what is often the focus for promoting change as mainly occurring through individual consciousness raising, important as this is, the concern of much mainstream deep ecology.

The purpose of this essay is to try and enlighten; to examine how the ecofascist term/concept has been used, and whether “ecofascism” has any conceptual validity within the radical environmental movement. I will argue that to be valid, this term has to be put in very specific contexts - such as anti-Nature activities as carried out by the “Wise Use” movement, logging and the killing of seals, and possibly in what may be called “intrusive research” into wildlife populations by restoration ecologists. Deep ecology supporters also need to be on guard against negative political tendencies, such as ecofascism, within this world view.

I will also argue that the social ecology-derived use of “ecofascist” against deep ecology should be criticized and discarded as sectarian, human-centered, self-serving dogmatism, and moreover, even from an anarchist perspective, totally in opposition to the open-minded spirit say of anarchist Emma Goldman. (See her autobiography Living My Life and in it, the account of the magazine she founded, Mother Earth.)

Fascism Defined

“Fascism” as a political term, without the “eco” prefix, carries some or all of the following connotations for me. I am using Nazi Germany as the model or ideal type:

- Overriding belief in “the Nation” or “the Fatherland or Motherland” and populist propaganda at all levels of the society, glorifying individual self-sacrifice for this nationalist ideal, which is embodied in “the Leader”.

- Capitalist economic organization and ownership, and a growth economy, but with heavy state/ political involvement and guidance. A social security network for those defined as citizens.

- A narrow and exclusive de facto definition of the “citizen” of the fascist state. This might exclude for example, “others” such as gypsies, jews, foreigners, etc. according to fascist criteria. Physical attacks are often made against those defined as “others”.

- No independent political or pluralistic political process; and no independent trade union movement, press or judiciary.

- Extreme violence towards dissenters, virulent anti-communism (communists are always seen as the arch enemy of fascism), and hostility towards those defined as on the “left”.

- Outward territorial expansionism towards other countries.

- Overwhelming dominance of the military and the state security apparatus.

What seems to have happened with “ecofascism”, is that a term whose origins and use reflect a particular form of human social, political and economic organization, now, with a prefix “eco”, becomes used against environmentalists who generally are sympathetic to a particular non-human centered and Nature-based radical environmental philosophy - deep ecology. Yet supporters of deep ecology, if they think about the concept of ecofascism, see the ongoing violent onslaught against Nature and its non-human life forms (plant life, insects, birds, mammals, etc.) plus indigenous cultures, which is justified as economic "progress”, as ecofascist destruction!

Perhaps many deeper environmentalists could foresee a day in the not too distant future when, unless peoples organize themselves to counter this, countries like the United States and its high consumptive lifestyle allies like Canada and other over‘developed’ countries, would try to impose a fascist world dictatorship in the name of “protecting their environment”and fossil fuel-based lifestyles. (The Gulf War for oil and the World Trade Organization indicate these hegemonic tendencies.) Such governments could perhaps then be considered ecofascist.

Social Ecology and Ecofascism

Since the mid 80's, some writers linked with the human-centered theory of social ecology, for example Murray Bookchin, have attempted to associate deep ecology with “ecofascism” and Hitler's “national socialist” movement. See his 1987 essay “Social Ecology Versus ‘Deep Ecology’” based on his divisive, anti-communist and sectarian speech to the National Gathering of the US Greens in Amherst Massachusetts (e.g. the folk singer Woody Guthrie was dismissed by Bookchin as “a Communist Party centralist”). There are several references by Bookchin in this essay, promoting the association of deep ecology with Hitler and ecofascism. More generally for Bookchin in this article, deep ecology is “an ideological toxic dump.”

Bookchin’s essay presented the view that deep ecology is a reactionary movement. With its bitter and self-serving tone, it helped to poison needed intellectual exchanges between deep ecology and social ecology supporters. This essay also outlined, in fundamental opposition to deep ecology, that in Bookchin’s social ecology there is a special role for humans. Human thought is “nature rendered self-conscious.” The necessary human purpose is to consciously change nature and, arrogantly, “to consciously increase biotic diversity.” According to Bookchin, social arrangements are crucial in whether or not the human purpose (as seen by social ecology) can be carried out. These social arrangements include a non-hierarchical society, mutual aid, local autonomy, communalism, etc. - all seen as part of the anarchist tradition. For social ecology, there do not seem to be natural laws to which humans and their civilizations must conform or perish. The basic social ecology perspective is human interventionist. Nature can be moulded to human interests.

Another ‘argument’ is to refer to some extreme or reactionary statement by somebody of prominence who supports deep ecology. For example, Bookchin calls Dave Foreman an "ecobrutalist”, and uses this to smear by association all deep ecology supporters - and to further negate the worth of the particular individual, denying the validity of their overall life's work. Foreman was one of the key figures in founding Earth First! He went on to do and promote crucial restoration ecology work in the magazine Wild Earth, which he helped found, and on the Wildlands Project. Overall he has, and continues to make, a substantial contribution. He has never made any secret of his right-of-center original political views and often showered these rightist views in uninformed comments in print, on what he saw as “leftists” in the movement. The environmental movement recruits from across class, although there is a class component to environmental struggles.

Bookchin’s comments about Foreman (of course social ecology is without blemish and has no need for self criticism!), are equivalent to picking up some backward and reactionary action or statement of someone like Gandhi, and using this to dismiss his enormous contribution and moral authority. Gandhi for example recruited Indians for the British side in the Zulu rebellion and the Boer War in South Africa; and in the Second World War in 1940, Gandhi wrote an astonishing appeal “To every Briton” counselling them to give up and accept whatever fate Hitler had for them, but not to give up their souls or their minds!

But Gandhi's influence remains substantial within the deep ecology movement, and particularly for someone like Arne Naess, the original and a continuing philosophical inspiration. Naess is dismissed by Bookchin as “grand Pontiff” in his essay.

Other spokespersons for social ecology, like Janet Biehl and Peter Staudenmaier, have later carried on this peculiar work. (See the 1995 published essays: “Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience” by Staudenmaier and Biehl; “Fascist Ecology: The ‘Green Wing’ of the Nazi Party and its Historical Antecedents” by Staudenmaier; and “‘Ecology’ and the Modernization of Fascism in the German Ultra-right” by Biehl.) For Staudenmaier and Biehl, in their joint essay: “Reactionary and outright fascist ecologists emphasize the supremacy of the ‘Earth’ over people.” Most deep ecology supporters would not have any problem identifying with what is condemned here. But this of course is the point for these authors.

Staudenmaier’s essay is quite thoughtful and revealing about some ecological trends in the rise of national socialism, but its ultimate purpose is to discredit deep ecology, the love of Nature and really the ecological movement, so it is ruined by its Bookchin-inspired agenda. For Staudenmaier, “From its very beginnings, then, ecology was bound up in an intensely reactionary political framework.” Basically this essay is written from outside the ecological movement. Its purpose is to discredit and assert the superiority of social ecology and humanism.

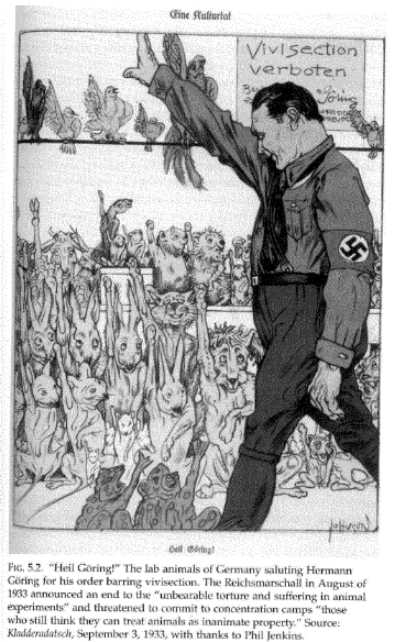

At its crudest, it is argued by such writers that, because SOME supporters of German fascism, liked being in the outdoors and extolled nature and the “Land” through songs, poetry, literature and philosophy and the Nazi dmovement drew from this, or because some prominent Nazis like Hitler and Himmler were allegedly “strict vegetarians and animal lovers”, or supported organic farming, this “proves” something about the direction deep ecology supporters are heading in. Strangely, the similar type argument is not made that because “socialist” is part of “national socialist”, this means all socialists have some inclination towards fascism! The writers by this argument also negate that the main focus of fascism and the Nazis was the industrial/military juggernaut, for which all in the society were mobilized.

Some ideas associated with deep ecology like the love of Nature; the concern with a needed spiritual transformation dedicated to the sharing of identities with other people, animals, and Nature as a whole; and with non-coercive population reduction (seen as necessary not only for the sake of humans but, more importantly, so other species can remain on the Earth and flourish with sufficient habitats), seem to be anathema to social ecology and are supposed to incline deep ecology supporters towards ecofascism in some way. Deep ecology supporters, contrary to some social ecology slanders, see population reduction, or perhaps controls on immigration, from a maintenance of biodiversity perspective, and this has nothing to do with fascists who seek controls on immigration or want to deport “foreigners” in the name of maintaining some so-called ethnic/cultural or racial purity or national identity.

A view is presented that only SOCIAL ecology can overcome the dangers these social ecology writers describe. Yet even this is wrong, although one can and should learn from this, I believe, important theoretical tendency. Deep ecology has the potential for a new economic, social, and political vision based on an ecocentric world view. Whereas all these particular social ecologists seem to be offering as the way forward, is a human-centered and non-ecological, anarchist social theory, pulled together from the past. Yet the basic social ecology premise is flawed, that human-to-human relations within society determine society's relationship to the natural world. This does not necessarily follow. Left biocentrism for example, argues that an egalitarian, non-sexist, non-discriminating society, while a highly desirable goal, can still be exploitive towards the Earth. This is why for deep ecology supporters, the slogan “Earth first” is necessary and not reactionary. Left biocentric deep ecology supporters believe that we must be concerned with social justice and class issues and the redistribution of wealth, nationally and internationally for the human species, but within a context of ecology. (See point 4 of the Left Biocentrism Primer.)

Deep ecology and social ecology are totally different philosophies of life whose fundamental premises clash! As John Livingston, the Canadian ecophilosopher put it, in his 1994 book Rogue Primate: An exploration of human domestication:

“It has become popular among adherents to ‘social ecology’ (a term

meaningless in itself, but apparently a brand of anarchism) to label those

who would dare to weigh the interests of Nature in the context of human

populations as ‘ecofascists.’”

Rudolf Bahro

The late deep-green German ecophilosopher and activist Rudolf Bahro (1935-1997) has been accused by some social ecology supporters - for example Janet Biehl, Peter Staudenmaier and others, without real foundation, of being an ecofascist and Nazi sympathizer and a contributor to “spiritual fascism”. Yet Bahro was a daring original thinker, who came into conflict with all orthodoxies in thought - particularly left and green orthodoxies. The language he used and metaphors as shown in his writings, display his considerable knowledge of European culture. But one would have to say that he took poetic license with his imagery - for example, the call for a “Green Adolf”. He saw this as perhaps necessary, to display the complexity of his ideas and to shake mass society from its

slumbers! But this helped to fuel attacks on him. Bahro was interested in concretely building a mass social movement and, politically incorrect as it may be, sought to see if there was anything to learn from the rise of Nazism: “How a millenary movement can be led, or can lead itself, and with what organs: THAT is the question.” (Bahro, Avoiding Social & Ecological Disaster, p.278)

This concern does not make him a fascist, particularly when one considers overall what he did with his life, his demonstrated deep sentiment for the Earth, and his various theoretical contributions. Bahro was also open-minded enough to invite Murray Bookchin and others with diverse views (for example the eco-feminist Maria Mies), to speak in his class at Humboldt University in East Berlin!

The social ecologist Janet Biehl, in her paper “‘Ecology’ and the Modernization of Fascism in the German Ultra-right”, has a four-page discussion on Rudolf Bahro. I come to the opposite conclusions about Bahro than she does. I see someone very daring, who raised spiritually-based questions on how to get out of the ecological crisis in a German context. Bahro was not a constipated leftist frozen in his thinking. Bahro saw that the left rejects spiritual insights. Biehl comes to the conclusion that Bahro, with his willingness to re-examine the national socialist movement, was giving “people permission to envision themselves as Nazis.”

Bahro, himself a person from the left, came to understand the role of left opportunists in undermining and diluting any deeper ecological understanding in Green organizations, in the name of paying excessive attention to social issues. They often called themselves “eco-socialists”, but never understood the defining role of ecology and what this means for a new radical politics. For many leftists, ecology was just an “add-on”, so there was no transformation of world view and consciousness was not changed. This is what happened in the German Green Party and Bahro combatted it. It therefore becomes important for those who see themselves as defending this left opportunism, to try to undermine Rudolf Bahro, the most fundamental philosopher of the fundamentalists. By 1985 Bahro had resigned from the Green Party saying that the members did not want out of the industrial system. Whatever Bahro’s later wayward path, the ecofascist charge needs to be placed in such a context.

Bahro did become muddled and esoteric in his thinking after 1984-5. This is shown, for example, by the esoteric/Christian passages to be found in Bahro’s last book published in English, Avoiding Social & Ecological Disaster: The Politics of World Transformation, and also by his involvement with the bankrupt Indian Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. Yet Bahro saw the necessity for a spiritual and eco-psychological transformation within society, something which social ecology does not support, to avoid social and ecological disaster.

Bahro, like Gandhi, believed it necessary to look inward, to find the spiritual strength to break with industrial society. This needed path is not invalidated by spiritual excess or losing one's way on the path.

As additional support for opposing the slander that Bahro was an ecofascist, I would advance the viewpoint of Saral Sarkar. He was born in India, but has lived in Germany since 1982. Sarkar was a radical political associate of Bahro (they were both considered “fundamentalists” within the German Greens) and fought alongside of him for the same causes. (Saral is also a friend who visited me in November/December of 1999 in Nova Scotia, Canada.) Although Sarkar writes with a subdued biocentric perspective, I would not consider him yet an advocate of deep ecology. But he does know Bahro’s work and the German context. Sarkar left the Green Party one year after Bahro. Sarkar, and his German wife Maria Mies, do not consider Bahro an ecofascist, although they both distanced themselves from Bahro’s later work. Sarkar has written extensively on the German Greens.

(See the two-volume Green-Alternative Politics in West Germany, published by the United Nations University Press, and his most recent book Eco-socialism or eco-capitalism? A critical analysis of humanity's fundamental choices, by Zed Books.)

Bahro was a supporter and, through his ideas, important contributor to the left biocentric theoretical tendency within the deep ecology movement. (See my “Tribute” to Bahro on his death, published in Canadian Dimension, March-April 1998, Vol. 32, No. 2 and elsewhere.) In a December 1995 letter, Bahro had declared that he was in agreement “with the essential points” of the philosophy of left biocentrism.

Legitimate Use of Ecofascism?

A. “Wise Use” [THIS IS A DISINGENUOUS ARGUMENT]

I mainly associate the term “ecofascism” in my own mind, with the so-called “Wise Use” movement in North America. (The goal is “use”, “wise” is a PR cover.) Essentially, “Wise Use” in this context means that all of Nature is available for human use. Nature should not be “locked up” in parks or wildlife reserves, and human access to “resources” always must have priority. One has in such “Wise Use” situations, what might be considered “traditional” fascist-type activities, used against those who are defending the ecology or against the animals themselves. This, in my understanding, makes for a legitimate use of the term ecofascist, notwithstanding what I have written above.

At a meeting in Nova Scotia in 1984 (an alleged Education Seminar organized by the Atlantic Vegetation Management Association), three ideologues of the “Wise Use” movement spoke - Ron Arnold, Dave Dietz and Maurice Tugwell. The message was “It takes a movement to fight a movement.” In other words, neither industry nor government according to Arnold, can successfully challenge a broadly based environmental movement. Hence the necessity for a “Wise Use” movement to do this work.

The fascist components of the “Wise Use” movement are:

- some popular misguided support of working people who depend on logging, mining,

fishing, and related exploitive industries who see their consumptive lifestyles threatened;

- backing by industrial capitalist economic interests linked to the same industries, who

provide money and political/media influence;

- the willingness to be influenced by hate propaganda, to demonize/scapegoat, and to use

violence and intimidation against environmentalists and their supporters;

- the tacit support of law enforcement agencies to “Wise Use” activities; and

- an unwillingness to publicly debate in a non coercive atmosphere the deeper

environmental criticism of the industrial paradigm, where old growth forests, oceans and

marine life, and Nature generally, only exist for industrial and human consumption.

In Canada, I see mainly two kinds of “Wise Use” activities. One concerns the actions of logging industry workers against environmentalists, for example in British Columbia, often concerning blocked access to logging old growth forests. Whereas the other ecofascist “Wise Use” activity is directed against seals mainly, and only secondarily against those who come forward to defend seals. So one “Wise Use” example is human-focussed and one is wildlife-focused. For a recent example of what could be called ecofascist activity, see the accounts of the physical attacks in September of 1999, by International Forest Products workers and others in the Elaho Valley in British Columbia, against environmentalists blockading a logging road, as reported in the Winter 1999 issue of the British Columbia Environmental Report and more fully in the December-January 2000 issue of the Earth First! Journal. These were ecofascist activities directed at environmentalists.

Another “Wise Use” ecofascist-type activity concerns the killing of seals, particularly on the east coast of Canada. There seems to be a hatred directed towards seals (and those who defend them), which extends from sealers and most fishers, to the corporate components of the fishing industry and the federal and provincial governments, particularly the Newfoundland and Labrador government (see for example, the extremely rabid “I hate seals” talk of provincial fisheries minister John Efford). The seals become scapegoats for the collapse of the ground fishery, especially cod. A vicious government-subsidized warfare, using all the resources of the state, becomes waged on seals. The largest annual wildlife slaughter in the world today concerns the ice seals (harp and hooded seals), which come every winter to the east coast of Canada to have their young and to mate. Quotas of 275,000 harps and 10,000 hoods, are allocated. Every honest knowledgeable person is aware that these quotas, given suitable ice killing conditions, are vastly exceeded. There is also a “hunt” with bounties, directed at grey seals, which live permanently in the Atlantic marine region.

In addition to the above, there are additional seal execution plans in the works. The so-called Fisheries Resource Conservation Council, in its April 1999 Report to the federal minister of fisheries giving as justification the protection of spawning and juvenile cod, seeks to:

- reduce seal herds by up to 50 percent of their current population levels;

- establish an experimental seal harvest for grey seals of up to 20,000 grey seals on Sable

Island; and

- define a limited number of so-called “seal exclusion” zones where all seals would be killed.

These zones seem to include the Northumberland Strait, the marine waters off New Brunswick

and Prince Edward Island and other areas.

I regard the pronouncements of the Fisheries Resource Conservation Council on seals as ecofascist mystification: “We need to kill seals for conservation”. I also regard as ecofascists those who actively work to remove seals from the marine eco-system because “there are far too many of them.”. (It seems that for such people there are never too many humans or fishers.)

With industrial capitalist societies having permanent growth economies, increasing populations, increasing consumerism as an intrinsic part of the economy, non-sustainable ecological footprints etc., and no willingness to change any of this, the struggle over what little wild Nature remains and whether it is going to be left alone or put to “use”, is becoming increasingly brutalized. Those who refuse to rise above suicidal short term interest, whether workers or capitalists, see themselves as having a stake in the continuation of industrial capitalism and are prepared to fiercely defend this at the expense of the ecology. Yet despite this “on the ground” reality which many environmental activists are facing, there seems to be an ongoing attempt to link the deep ecology movement and its supporters with ecofascism - that is, to malign some of the very people who are experiencing ecofascist attacks!

B. Intrusive Research

Another example of where the term “ecofascist” can be applied, will be much more controversial within the deep ecology movement, since it is directed at some in our own ranks - that is, some of those who work in the field of conservation biology! The ecofascist activity here is directed at wildlife, not humans. But I have come to believe it to be true, and that it is necessary to speak out about it. It concerns in a general way, Point 4 of the Deep Ecology Platform (by Arne Naess and George Sessions), “Present human interference with the nonhuman world is excessive, and the situation is rapidly worsening.”

Specifically it concerns activities carried out by conservation biologists which can be called “intrusive research” into wildlife populations. This is generally done in the name of restoration ecology. (Of course, industrialized society and its supporters inflict far worse intrusive horrors, for example, on domestic animals destined for the food machine.)

In a sense wildlife becomes “domesticated” by some conservation biologists, so that it can be numbered, counted, tagged, and manipulated. This does not appear, so far, to have been challenged from a deep ecology perspective. Conservation biology, like any other profession, if looked at sociologically, has its own taken-for-granted world view justifying its existence. The world view seems to be, not that “Nature knows best,” but that “Nature needs the interventions of conservation biologists to rectify various ecological problems.”

The intrusive research practices engaged in by some conservation biologists and traditional “fish and game” biologists, seem to be remarkably similar. They both use computer-type and other technologies, such as radio-collars, implanted computer chips, banding, etc. The main defense of intrusive research seems to be two-fold:

- the first is that habitat is crucial for wild animals (no disagreement here), and that radio-collaring and the use of other tracking and computerized devices have been helpful in establishing the ranges of the wild animals being studied. (But there are other non intrusive

methods, although more labour and knowledge intensive, for the range tracking of wildlife.)

- the second justification, the one that I feel has some ecofascist echos, is that “the larger good” requires such research and any negatives to the “researched” animals have to be accepted from this perspective. (This larger good is defined variously as the goals of the Wildlands Project; the health of the wildlife populations being studied; the well being of the ecosphere; or work towards implementing the goals of the Deep Ecology Platform.) One thinks here of the fascist goals of “the nation” or “the fatherland” as justification to sacrifice the individual human or groups of humans considered expendable. For me, the defense of intrusive research on nonhuman life forms and their expendability, in the name of a human-decided larger good, although couched in ecological language, is the ultimate anthropocentrism and could legitimately be called an example of ecofascism.

I have to come to see that, as well as working for conservation, it is necessary to work for the individual welfare of animals. This is an important contribution and lesson from the animal rights or animal liberation movement. Animal welfare, as well as the concern with species or populations and the preservation of habitat, must be part of any acceptable restoration ecology.

C. Inducing Fear

Perhaps another example of ecofascist behaviour which could occur within our own ranks might be carrying out activities which could deliberately kill or injure people in the name of some environmental or animal rights/animal liberation cause. This seems to rest on using “fear” to destabilize. Many activists of course know that the state security forces also have successfully used such tactics to try and discredit the radical animal rights and radical environmental movements.

More important philosophically perhaps, such activities may rest on the deeper view that in the chain of life, the human species does not have a privileged status above other species, and must be held accountable for anti-life behaviours. In other words, why should violence be acceptable towards nonhuman species, and non-violence apply only to humans? We also know that any state, whatever its ideological basis, claims a monopoly on the use of violence against its citizens and will use all its institutions to defend this. Yet the term “terrorist” is only applied against opponents of the prevailing system. Also, many activists have experienced “terror” from the economic growth and high consumption defenders. However, the political reality is that the charge of “ecoterrorist”, often used as a blanket condemnation against radical environmentalists and animal rights activists, seems to be fed by such behaviour of attempting to induce fear.

Conclusion

This bulletin has shown that the concept of “ecofascism” can be used in different ways. It has looked at how some social ecology supporters have used this term in a basically unfounded manner to attack deep ecology and the ecological movement, and it also looked at what can be called ecofascist attacks against the environmental movement. So we can say that the term “ecofascism” can be used:

- Illegitimately. This is the use of the term which has been advanced by some social ecologists who have tried to link those who defend the Natural world, particularly deep ecology supporters, with traditional fascist political movements - especially the Nazis. The “contribution” of these particular social ecologists has been to thoroughly confuse what ecofascist really means and to slander the new thinking of deep ecology. This seems to have been done from the viewpoint of trying to discredit what some social ecologists apparently see as an ideological ‘rival’ within the environmental and green movements. This social ecology sectarianism has resulted in ecofascism becoming an attack term against those environmentalists who are out in the trenches being attacked by real ecofascists! I have also defended the late Rudolf Bahro against the charge of being an ecofascist or Nazi sympathizer.

- Legitimately, to describe “Wise Use” type activities, that is, against those who want to

exploit Nature until the end, solely for human/corporate purposes, and who will do whatever

is seen as necessary, including using violence and intimidation against environmentalists and

their supporters, to carry on. We should not be phased by “Wise Use” supporters calling

their ecodefender opponents ecoterrorists, or saying that they themselves are “the true

environmentalists.” This is merely a diversion. Also I have raised in this bulletin for discussion, what seem to me to be some real contradictions within the deep ecology camp itself around the ecofascism issue, e.g. intrusive research.

Hopefully this article will also enable deep ecology supporters to be less defensive about the terms ecofascist or ecofascism. These terms, if rescued from social ecology-inspired obfuscation, do have analytical validity. They can be used against those destroyers of the Natural world who are prepared to use violence and intimidation, and other fascist tactics, against their opponents.

[THIS ARTICLE OBVIOUSLY IS INSINCERE, DISINGENUOUS, AND AN EFFORT TO CONFUSE THE PUBLIC ABOUT WHAT ECO-FASCISM, ECO-TERRORISM AND ECO-ABSOLUTISM REALLY ARE ABOUT]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

http://www.eoearth.org/article/Deep_ecology

Deep ecology

By David Landis Barnhill

Table of Contents

1 Introduction

2 Three meanings of the term 'deep ecology'

3 Common characteristics of deep ecology

4 Debating deep ecology

5 Further Reading

This article has been reviewed and approved by the following Topic Editors: Sahotra Sarkar (other articles) and Linda Kalof (other articles)

November 5, 2006

Introduction

Deep ecology is one of the principal schools in contemporary environmental philosophy. The term was first used by the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess in 1972 in his paper "The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movement." The term was intended to call for a fundamental rethinking of environmental thought that would go far beyond anthropocentric (human-centered) and reform environmentalism that sought merely to adjust environmental policy. Instead of limiting itself to the mitigation of environmental degradation and sustainability in the use of natural resources, deep ecology is self-consciously a radical philosophy that seeks to create profound changes in the way we conceive of and relate to nature.

Three meanings of the term 'deep ecology'

The term 'deep ecology' has been used in three main ways. First, it refers to a deep questioning about environmental issues. It probes the fundamental causes of environmental problems and the underlying worldview of environmental policies. In this it follows the view of historian Lynn White, who argued that environmental problems are rooted in religious worldviews and that real solutions must involve a change at that fundamental level. Assumptions about the value of nature and the relationship between humans and the natural world, for instance, shape the way we view and interact with nature. Deep ecology is “deep” because it reflects critically on those fundamental assumptions. In this sense, deep ecology refers to any environmental philosophy that critiques deep-seated worldviews and proposes a radical alternative.

Second, deep ecology refers to a platform, first formulated as eight principles by Arne Naess and George Sessions in 1984. Those principles are as follows:

The well-being and flourishing of human and nonhuman life on Earth have value in themselves (synonyms: intrinsic value, inherent value). These values are independent of the usefulness of the nonhuman world for human purposes.

Richness and diversity of life forms contribute to the realization of these values and are also values in themselves.

Humans have no right to reduce this richness and diversity except to satisfy vital needs.

The flourishing of human life and cultures is compatible with a substantial decrease of the human population. The flourishing of nonhuman life requires such a decrease.

Present human interference with the nonhuman world is excessive, and the situation is rapidly worsening. Policies must therefore be changed. These policies affect basic economic, technological, and ideological structures. The resulting state of affairs will be deeply different from the present.

The ideological change is mainly that of appreciating life quality (dwelling in situations of inherent value) rather than adhering to an increasingly higher standard of living. There will be a profound awareness of the difference between big and great.

Those who subscribe to the foregoing points have an obligation directly or indirectly to try to implement the necessary changes.

The intent of this platform is to articulate central views and values that a variety of schools of environmental thought could agree on. Various worldviews, from Buddhism to ecosocialism, could be the foundation of these principles, and the principles could be put into practice in divergent ways. In this sense, deep ecology specifies a common philosophic core while remaining open to a pluralism of worldviews and policies.

The third and most common meaning of the term deep ecology is a philosophy of nature that are in line with this platform but are more specific in their views and values. Deep ecology in this sense refers to the views of environmental philosophers such as Arne Naess and Warwick Fox, in contrast to the views found in ecofeminism and social ecology. This restricted sense of deep ecology is characterized by the following principles:

Holism. Nature is seen holistically, as an integrated system, rather than as a collection of individual things. The “oneness” of nature, however, is not monistic, denying the reality of individuals and difference. Rather, the natural world consists of an organic wholeness, a dynamic field of interaction of diverse species and their habitats. In fact, that diversity is essential to the health of the natural world. No ontological divide. Humans are fully a part of nature, and there is no ontological separation between our species and other ones.

Self. Individually, each person is not an autonomous individual but rather a self-in-Self, a distinct node in the web of nature.

Biocentric egalitarianism. Nature has unqualified intrinsic value, with humans having no priveleged place in nature's web. Emphasis is placed on value at holistic levels, such as populations, ecosystems, and the Earth as a whole, rather than individual entities.

Intuition. A sensuous, intuitive communion with the Earth is possible, and it gives us needed insight into nature and our relationship to it. Scientific knowledge is necessary and useful, but we need a holistic science that recognizes the intrinsic value of the Earth and our interdependence with it. Environmental devastation. Nature is undergoing a cataclysmic degradation, an ecological holocaust, at the hands of human societies.

Anti-anthropocentrism. This destructiveness is rooted in anthropocentrism, an arrogant view that we are separate from and superior to nature, which exists to serve our needs.

An ecocentric society. The goal at a social level is a society that is based on an ecocentric view of nature and that lives in harmony with the natural tendencies and the limits of natural world.

Self-realization. The goal at an individual level is to fully realize one’s identification with nature. This involves neither a sense of an independent self nor the loss of the self in the oneness of nature. Self-realization is the full awareness of the self-in-Self.

Intuitive morality. The moral ideal, then, does not involve ethics in the traditional sense of a separate self rationally deriving principles of how we ought to behave. Rather, it is a realization of our identification with nature which yields a spontaneous, intuitive tendency to avoid harm and to flourish. As John Seed has said of his work on the rainforest, “I am the rainforest defending itself.”

Common characteristics of deep ecology

One of the common characteristics of deep ecology is the valorization of wilderness. Since nature is being destroyed by human exploitation and manipulation, the ideal is to be found in areas in which there has been virtually no such use and control. In wilderness areas we see how nature works without human interference, flourishing with a complex and spontaneous order. In addition, in wilderness we recognize ourselves as but a small part of the vast richness of the natural world. For some deep ecologists, this has lead to a critical attitude toward agriculture as another instance of humans manipulating the Earth for their own ends. By contrast, hunting and gathering—gathering nature’s riches rather than controlling it—has been seen by some as an ideal human use of nature.

Another characteristic of deep ecology is a tendency to draw on the religions of other cultures. Buddhism and Native American spirituality have been particularly strong influences on deep ecology. Daoism and Hinduism have also been influential. In addition, certain Western philosophers, such as Baruch Spinoza and Martin Heidegger, have played an important role in the development of deep ecology. Also central to deep ecology have been certain poets and nature writers, such as John Muir, Robinson Jeffers, and Gary Snyder. In fact, deep ecology can be seen as a contemporary development of the preservationism first espoused by Muir. The holistic and biocentric environmental philosophy of Aldo Leopld has also been influential, and deep ecology accepts Leopold's famous statement in "The Land Ethic": “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

Debating deep ecology

Deep ecology began as a critique of the “shallow ecology” of anthropocentric conservationism, epitomized by Gifford Pinchot, who saw the Earth as a set of natural resources that need to be managed for present and future generations of humans. Deep ecologists also tend to criticize the reformist environmentalism exemplified by large, mainstream environmental organizations that work within the political system to gain policy victories without challenging society’s main assumptions and values that are the ultimate cause of environmental degradation. Some deep ecologists also have criticized the animal rights movement as maintaining an implicitly anthropocentric view that extends human rights to at least some animals, and in so doing upholding a hierarchical view of nature (animals are more important than plants). They also object to the individualist approach common among animal liberationists, which they believe neglects the importance of whole systems.

There has been a vigorous, and at times shrill, debate between proponents of deep ecology and other schools of radical environmental thought. Ecofeminism has criticized deep ecology for neglecting the close ties between environmental thought and social ideology, especially the long-standing tendency to associate nature with the female and then devaluing and oppressing both. Similarly, it has criticized deep ecology’s general neglect of social problems that are caused by the logic of domination, in which some social groups are assumed to have more value and have the right to control and use others, the same logic of domination that fuels environmental destruction. In addition, ecofeminists have argued that a biocentric philosophy that ignores social injustice is not acceptable. There has also been a deep suspicion of deep ecology’s accounts of self-realization and oneness with nature, which have seemed to some ecofeminists as a metaphysical aggrandizement of the male ego as well as a holism that diminishes the value of the individual and relationships. Some of these criticisms have been based on representing deep ecology with extreme positions that are not emblematic of the central thrust of deep ecology. However, many of the criticisms have been powerful and resulted in clarifications and refinements in deep ecology philosophy. Many contemporary deep ecologists are deeply concerned about these social issues and have articulated a holism that does not diminish the reality or value of individuals and their relationships.

Social ecologists and ecosocialists have made similar critiques of deep ecology's neglect of the social dimension of environmental problems. They have in particular accused deep ecologists of neglecting issues of class and race. In addition, they have argued that deep ecology overlooks the significance of authoritarianism, hierarchy, and the nation-state as causes of environmental and social problems. Merely focusing on changing worldviews and living lightly on the land leaves the structures of power free to ravage the planet and oppress human society. Some have also been suspicious of deep ecology spirituality, which they see as irrational, superficial, and inauthentic. In turn, deep ecologists have expressed concern that the emphasis on human society by ecofeminists, social ecologists, and ecosocialists can signal a regression to anthropocentrism. And they point out that it is quite possible to have a society that exhibits social justice while devaluing and abusing the environment. However, as in the case of ecofeminism, some of the criticisms by social ecologists and ecosocialists have exposed important weaknesses in deep ecology and lead to a more comprehensive view.

In some cases, these debates have been unnecessarily antagonistic, reflecting an unbending sectarianism that fails to recognize the possibility of bringing together insights from various schools of thought. Other writers, on the other hand, have shown how different approaches can be enriched by being open to each other’s views. Roger S. Gottlieb has persuasively argued that deep ecology spirituality is compatible with keen social analysis and pragmatic political activism. John Clark has shown that social ecology and deep ecology can learn from each other. Stephanie Kaza has demonstrated that there can be a deep ecological ecofeminism. And Gary Snyder, often considered an icon of deep ecology, has significant elements of social ecology and ecofeminism in his writings.

Further Reading

Barnhill, David Landis, and Roger S. Gottlieb, eds. Deep Ecology and World Religion: New Essays on Sacred Ground. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001.

Devall, Bill, and George Sessions. Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered. Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith, 1985.

Drengson, Alan, and Yuichi Inoue, eds. The Deep Ecology Movement: An Introductory Anthology. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 1995.

Fox, Warwick. Toward a Transpersonal Ecology: Developing New Foundations for Environmentalism. Boston: Shambhala, 1990.

Katz, Eric, Andrew Light, and David Rothenberg, eds. Beneath the Surface: Critical Essays in the Philosophy of Deep Ecology. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 2000.

Naess, Arne. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy. Trans. and ed. by David Rothenberg. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

Sessions, George, ed. Deep Ecology for the 21st Century. Boston: Shambhala, 1995.

Snyder, Gary. The Practice of the Wild. San Francisco: North Point Press, 1990.

Zimmerman, Michael E. Contesting Earth's Future: Radical Ecology and Postmodernity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Citation

Barnhill, David Landis (Lead Author); Sahotra Sarkar and Linda Kalof (Topic Editors). 2006. "Deep ecology." In: Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. Cutler J. Cleveland (Washington, D.C.: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment). [First published in the Encyclopedia of Earth October 11, 2006; Last revised November 5, 2006; Retrieved April 7, 2008]. http://www.eoearth.org/article/Deep_ecology

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

http://www.clas.ufl.edu/users/bron/PDF--Christianity/Taylor+Zimmerman--Deep%20Ecology.pdf

Deep Ecology

Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess (b. 1912) coined the term “Deep Ecology” in 1972 to express the ideas that nature has intrinsic value, namely, value apart from its usefulness to human beings, and that all life forms should be allowed to flourish and fulfill their evolutionary destinies. Naess invented the rubric to contrast such views with what he considered to be “shallow” environmentalism, namely, environmental concern rooted only in concern for humans. The term has since come to signify both its advocates’ deeply felt spiritual connections to the earth’s living systems and ethical obligations to protect them, as well as the global environmental movement that bears its name. Moreover, some deep ecologists posit close connections between certain streams in world religions and deep ecology. Naess and most deep ecologists, however, trace their perspective to personal experiences of connection to and wholeness in wild nature, experiences which are the ground of their intuitive, affective perception of the sacredness and interconnection of all life. Those who have experienced such a transformation of consciousness (experiencing what is sometimes called one’s “ecological self” in these movements) view the self not as separate from and superior to all else, but rather as a small part of the entire cosmos. From such experience flows the conclusion that all life and even ecosystems themselves have inherent or intrinsic value – that is, valueindependently of whether they are useful to humans. Although Naess coined the term, many deep ecologists credit the American ecologist Aldo Leopold with succinctly expressing such a deep ecological worldview in his now famous “Land Ethic” essay, which was published posthumously in A Sand County Almanac in 1948.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 2

Leopold argued that humans ought to act only in ways designed to protect the long-term flourishing of all ecosystems and each of their constituent parts. Many deep ecologists call their perspective alternatively “ecocentrism” or “biocentrism”(to convey, respectively, an ecosystem-centered or life-centered value system). As importantly, they believe humans have so degraded the biosphere that its life-sustaining systems are breaking down. They trace this tragic situation to anthropocentrism (human-centeredness), which values nature exclusively in terms of its usefulness to humans. Anthropocentrism, in turn, is viewed as grounded in Western religion and philosophy, which many deep ecologists believe must be rejected (or a deep ecological transformation of consciousness within them must occur) if humans are to learn to live sustainable on the earth. Thus, deep ecologists generally believe that only by “resacralizing” our perceptions of the natural world can we put ecosystems above narrow human interests and thereby avert ecological catastrophe by learning to live harmoniously with the natural world.

It is a common perception within the deep ecology movement that the religions of indigenous cultures, theworld’s remnant and newly revitalized or invented pagan religions, and religions originating in Asia (especially Taoism, Buddhism, and Hinduism), provide superior grounds for ecological ethics, and greater ecological wisdom, than do Occidental religions.

Theologians such as Matthew Fox and Thomas Berry, however, have shown that Western religions such as Christianity may be interpreted in ways largely compatible with the deep ecology movement. Although Naess coined the umbrella term, which is now a catchphrase for most non-anthropocentric environmental ethics, a number of Americans were also criticizing anthropocentrism and laying the foundation for the movement’s ideas, at about the same time as Naess was coining the term. One crucial event early in deep ecology’s evolution was the 1974 2

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 3

“Rights of Non-Human Nature” conference held at a college in Claremont, California. Inspired by Christopher Stone’s influential 1972 law article (and subsequent book) Should Trees Have Standing– Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects the conference drew many of those who would become the intellectual architects of deep ecology. These included George Sessions who, like Naess, drew on Spinoza’s pantheism, later co-authoring Deep Ecology with Bill Devall; Gary Snyder, whose remarkable, Pulitzer prize-winning Turtle Island proclaimed the value of place-based spiritualities, indigenous cultures, and animistic perceptions, ideas that would become central within deep ecology subcultures; and the late Paul Shepard (d. 1996), who in The Tender Carnivore and the Sacred Game, and subsequent works such as Nature and Madness and the posthumously published Coming Back to the Pleistocene, argued that foraging societies were ecologically superior to and emotionally healthier than agricultures. Shepard and Snyder especially provided a cosmogony that explained humanity’s fall from a pristine, nature paradise. Also extremely influential was Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire, which viewed the desert as a sacred place uniquely able to evoke in people a proper, non-anthropocentric understanding of the value of nature.

By the early 1970s the above figures put in place the intellectual foundations of deep ecology. A corresponding movement soon followed and grew rapidly, greatly influencing grassroots environmentalism, especially in Europe, North America, and Australia. Shortly after forming in 1980, for example, leaders of the politically radical Earth First! movement (the explanation point is part of its name) learned about Deep Ecology, and immediately embraced it as their own, spiritual, philosophy. Meanwhile, the green lifestyle-focused movement known as Bioregionalism became another physical embodiment of a deep ecology worldview. Given their3

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 4

natural affinities it was not long before Bioregionalism became the prevailing social philosophy among deep ecologists. As a philosophy and as a movement, deep ecology spread in many ways.

During the 1980s and early 1990s, for example, Bill Devall and George Sessions published their influential book, Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered; Warwick Fox in Toward a Transpersonal Ecology linked deep ecology with transpersonal psychology, thereby furthering the development of what is now called “ecopsychology”; David Rothenberg translated and edited Arne Naess’simportant work, Ecology, Community and Lifestyle; and Michael E. Zimmerman interpreted Martin Heidegger as a forerunner of deep ecology, thus helping to spark a trend of calling upon contemporary European thinkers for insight into environmental issues. Many deep ecologists have complained, however, that the postmodern thinking imported from Europe has undermined the status of “nature,” defined by deep ecologists as a whole that includes but exists independently of humankind.

Radical environmentalist activists, including the American co-founder of Earth First!, Dave Foreman, and the Australian co-founder of the Rainforest Information Centre, John Seed, beginning in the early 1980s, conducted “road shows” to transform consciousness and promote environmental action. Such events usually involve speeches and music designed to evoke or reinforce peoples felt connections to nature, and inspires action. Often, they also include photographic presentations contrasting sacred, intact, ecosystems, which are contrasted with degraded and defiled lands. Some activists have designed ritual processes to further deepen participant’s spiritual connections to nature and political commitment to defend it. Joanna Macy and a number of others, including John Seed, for example, developed a ritual process known as the Council of All4

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 5

Beings, which endeavors to get activists to see the world from the perspective of non-human entities. Since the early 1980s, traveling widely around the world, Seed has labored especially hard spreading deep ecology through this and other newly invented ritual processes. The movement has also been disseminated through the writings of its architects (often reachingcollege students in environmental studies courses); through journalists reporting on deep ecology-inspired environmental protests and direct action resistance; and through the work of novelists, poets, musicians, and other artists, who promote in their work deep ecological perceptions. Recent expressions in ecotourism can be seen, for example, in the “Deep Ecology Elephant Project,” which includes tours in both Asia and Africa, and suggest that elephants and other wildlife have much to teach their human kin.

Deep Ecology has been criticized by people representing social ecology, socialistecology, liberal democracy, and ecofeminism. Murray Bookchin, architect of the anarchistic green social philosophy known as Social Ecology, engaged in sometimes vituperative attacks on deep ecology and its activist vanguard, Earth First!, for being intellectually incoherent, ignorant of socio-economic factors in environmental problems, and given to mysticism and misanthropy. Bookchin harshly criticized Earth First! co-founder Dave Foreman for suggesting that starvation was a solution to human overpopulation and environmental deterioration. Later, however, Bookchin and Foreman engaged in a more constructive dialogue. Like social ecologists, meanwhile, socialist ecologists maintain that deep ecology overemphasizes cultural factors (worldviews, religion, philosophy) in diagnosing the roots of, and solutions to, environmental problems, thereby minimizing the roles played by the social, political, and economic factors inherent in global capitalism. 5

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 6

Liberal democrats such as the French scholar Luc Ferry (1995) maintain that deep ecology is incapable of providing guidance in moral decision-making. Insofar as deep ecology fails adequately to recognize that human life has more value than other life forms, he argues, it promotes ‘ecofascism,’ namely the sacrifice of individual humans for the benefit of the ecological whole, what Leopold termed “the land.” (Ecofascism in its most extreme form links the racial purity of a people to the well-being of the nation’s land; calls for the removal or killing of non-native peoples; and may also justify profound individual and collective sacrifice of its own people for the health of the natural environment.)

Many environmental philosophers have defended Leopold’s land ethic, and by extension, deep ecology, against such charges, most notably one of the pioneers of contemporary environmental philosophy, Baird Callicott. Although some ecofeminists indicate sympathy with deep ecology’s basic goal, namely, protecting natural phenomena from human destruction, others have sharply criticized deep ecology. Male, white, and middle class deep ecologists, Ariel Salleh maintains, ignore how patriarchal beliefs, attitudes, practices, and institutions help to generate environmental problems. Val Plumwood and Jim Cheney criticize deep ecology’s idea of expanding the self so as to include and thus to have a basis for protecting non-human phenomena. This “ecological self” allegedly constitutes a totalizing view that obliterates legitimate distinctions between self and other. Moreover, Plumwood argues, deep ecology unwisely follows the rationalist tradition in basing moral decisions on “impartial identification,” a practice that does not allow for the highly particular attachments that often motivate environmentalists and indigenous people alike to care for local places. Warwick Fox has replied that impartial and wider identification does not cancel out particular or personal attachments, but instead, puts them in the context of more encompassing 6

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 7

concerns that are otherwise ignored, as when for example concern for one’s family blinds one to concerns about concerns of the community. Fox adds that deep ecology criticizes the ideology—anthropocentrism—that has always been used to by social agents to legitimate oppression of groups regarded as sub- or non-human. While modern liberation movements have sought to include more and more people into the class of full humans, such movements have typically not criticized anthropocentrism as such. Even a fully egalitarian society, in other words, could continue to use anthropocentrism to justify exploiting the non-human realm.In response to the claim that deep ecology is, or threatens to be, a totalizing worldview that excludes alternatives and that—ironically—threatens cultural diversity, Arne Naess responds that, to the contrary, deep ecology is constituted by multiple perspectives or “ecosophies” (ecological-philosophies) and is compatible with a wide range of religious perspectives andphilosophical orientations. Another critic, best-selling author Ken Wilber, argues that by portraying humankind as merely one strand in the web of life, deep ecology adheres to a one-dimensional, or “flatland”metaphysics (1995).

Paradoxically, by asserting that material nature constitutes the whole of which humans are but a part, deep ecologists agree in important respects with modern naturalism, according to which humankind is a clever animal capable of and justified in dominating other life-forms in the struggle for survival and power. A “deeper” ecology would follow from discerning that the cosmos is hierarchically ordered in terms of complexity, but that respect and compassion are due all phenomena because they are manifestations of the divine. In the last analysis, for Naess, it is personal experiences of a spiritual connection with nature and related perceptions of nature’s inherent worth or sacredness, which provide the ground for deep ecological commitments. In his view, such experiences are diverse and this 7

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 8

approach respects diversity, indeed, many ultimate premises are consistent with the eight-point, Deep Ecology Platform, which Naess developed with George Sessions.

Although controversial and contested, both internally and among its proponents and its critics, Deep Ecology is an increasingly influential green spirituality and ethics that universally recognized in environmentalist enclaves, and increasingly outside of such subcultures, assignifying a radical movement that challenges the conventional, usually anthropocentric ways humans deal with the natural world. Its influence in environmental philosophy has been profound, for even those articulating alternative environmental ethics are compelled to respond to its insistence that nature has intrinsic and even sacred value, and its anti-anthropocentric challenge.

Its greatest influence, however, may be through the diverse forms of environmental activism that it inspires, action that increasingly shapes world environmental politics. Not only is deep ecology the prevailing spirituality of bioregionalism and radical environmentalism, it undergirds the International Forum on Globalization and the Ruckus Society, two organizations playing key roles in the anti-globalization protests that erupted in 1999. Both of these groups are generously funded by the San Francisco-based Foundation for Deep Ecology, and other foundations, which share deep ecological perceptions. Such developments reflect a growing impulse toward institutionalization, which isdesigned to promote deep ecology and intensify environmental action. There are now Institutes for Deep Ecology in London, England and Occidental, California, a Sierra Nevada Deep Ecology Institute in Nevada City, California, and dozens of other organizations in the United States,Oceania, and Europe, which provide ritual-infused experiences in deep ecology and training forenvironmental activists. It is not, however, the movement’s institutions, but instead the8

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 9

participants’ love for the living Earth, along with their widespread apocalypticism (their conviction that that the world as we know it is imperiled or doomed), that give the movement its urgent passion to promote earthen spirituality, sustainable living, and environmental activism.

Bron Taylor, University of Wisconsin Oshkosh

Michael Zimmerman, Tulane University

Abbey, Edward. Desert Solitaire. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. 1988.

Further Reading:

Abram, David. Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. New York: Pantheon. 1996.

Barnhill, David and Roger Gottlieb. Deep Ecology and World Religions. Albany: SUNY Press. 2001

Bookchin, Murray. Social Ecology versus ‘Deep Ecology.’ Green Perspectives (4 & 5, Summer1987).

Bookchin, Murray and Dave Foreman. Defending the Earth. Boston: South End Press. 1991.

Callicott, J. Baird. Holistic Environmental Ethics and the Problem of Ecofascism. Beyond the 9

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 10

Land Ethic: More Essays in Environmental Philosophy. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. 1999. Cheney, Jim. “Eco-Feminism and Deep Ecology.” Environmental Ethics 9 (Summer 1987), 115-145. Devall, Bill. Simple in Means, Rich in Ends: Practicing Deep Ecology. Salt Lake City, UT: Peregrine Smith. 1988. Devall, Bill and George Sessions. Deep Ecology: Living As If Nature Mattered. Salt Lake City, UT: Peregrine Smith. 1985. Drengson, Alan, and Yuichi Inoue, eds. The Deep Ecology Movement: An IntroductoryAnthology. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic. 1995. Ferry, Luc. The New Ecological Order. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1995. Fox, Matthew. The Coming of the Cosmic Christ: The Healing of Mother Earth and the Birth of a Global Renaissance. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988. Fox, Warwick. “The Deep Ecology—Ecofeminism Debate and Its Parallels.” Environmental Ethics. 11 (Spring 1989), 5-25. Fox, Warwick. Toward a Transpersonal Ecology. Boston: Shambhala. 1990. 10

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 11

Katz, Eric, Andrew Light, and David Rothenberg. Beneath the Surface: Beneath the Surface: Critical Essays on Deep Ecology. Cambridge: The MIT Press. 2000.

LaChapelle, Dolores. Earth Wisdom. Silverton, Colorado: Finn Hill Arts. 1978.

LaChapelle, Dolores. Sacred Land, Sacred Sex: Rapture of the Deep. Silverton, Colorado: Finn Hill Arts. 1988.

Macy, Joanna. World As Lover, World As Self. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press. 1991.

Manes, Christopher. Green Rage: Radical Environmentalism and the Unmaking of Civilization, Boston: Little, Brown, 1990.

Naess, Arne. “The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movement: A Summary.”Inquiry 16 (1973), 95-100.

Naess, Arne. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle, ed. D. Rothenberg, trans. D. Rothenberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1989.

Plumwood, Val. “Nature, Self, and Gender: Feminism, Environmental Philosophy, and theCritique of Rationalism.” Hypatia. 6 (Spring 1991), 3-27. 11

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 12

Salleh, Ariel. “The Ecofeminism/Deep Ecology Debate: A Reply to Patriarchal Reason.” Environmental Ethics 3 (Fall 1992), 195-216.

Seed, John, Joanna Macy, Pat Fleming, and Arne Naess. Thinking Like a Mountain: Towards a Council of All Beings. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: New Society. 1988.

Sessions, George, ed. Deep Ecology for the 21st Century. Boston: Shambhala Publications. 1995.

Shepard, Paul. Coming Home to the Pleistocene. San Francisco: Island Press. 1998. Snyder, Gary. Turtle Island. New York: New Directions. 1969.

Snyder, Gary. The Practice of the Wild. San Francisco: North Point Press. 1990.

Taylor, Bron, ed. Ecological Resistance Movements: The Global Emergence of Radical and Popular Environmentalism. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. 1995.

Taylor, Bron, “Deep Ecology As Social Philosophy: A Critique.” In Eric Katz, Andrew Light and David Rothenberg, eds. Beneath the Surface: Critical Essays on Deep Ecology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2000, 269-99.

Tobias, Michael, ed. Deep Ecology. San Diego: Avant Books. 1985.

Zimmerman, Michael E. “Toward a Heideggerean Ethos for Radical Environmentalism.” 12

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page 13

13Environmental Ethics 5 (Summer 1983): 99-132. Zimmerman, Michael E. “Rethinking the Heidegger—Deep Ecology Relationship.” Environmental Ethics 15 (Fall 1993), 195-224. Zimmerman, Michael E. Contesting Earth’s Future: Radical Ecology and Postmodernity.Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994.

No comments:

Post a Comment